“Vers la fin de l année 1761, le Regiment de mont marin dans lequel je servais en qualité de Capitaine, était en garrison a Bordeaux…; il recut ordre de se tenir prêt pour s embarquer sur les vaisseaux du Roy a Rochefort pour etre transporté a l Amerique.”

Of all the people who used to come to tea at La Tourbeille, Madame V. was my favorite. Sparkling and direct, she prefers cheer to gloom and had the best stories about life in this region during the Time Before the War. I shunned all other conversation to glue myself to her side for tales of blissful childhood summers punctuated by afternoon “receptions,” one scheduled each day of the week at her relative’s properties in the vicinity. She ticked them off as if it were yesterday: “Monday was Bellevue, Tuesday Ribebon, Wednesday Piquetterie, Thursday La Tourbeille – Patrice (the then owner, our great uncle) was very nice but so busy with the vineyard he rarely attended his own parties…”

It was easy to picture the La T parties: silk dresses and feather trimmed hats, (we found them in a steamer trunk in the attic along with L.’s notes: “last silk manufacture of Lyon before the War”) tea sipped from 1840’s Sevres or hot chocolate poured from an ornate silver samovar (since relegated to dust-gathering in the back of the dining room cupboards) white damask tablecloths piled high with cakes, (recipes now stained with butter and age, preserved in the kitchen closet) followed by croquet and bridge games and conversations about the rise of Germany. It must have been a coveted venue for young people to overcome country doldrums and meet other young people; for Parisian cousins to escape the city smog for a month of pastoral invitations.

Of course the War put paid all that. Madame V.’s young husband was captured in duty, then escaped after several months in a camp. By the time he made it home the Germans had taken over most of France. When we got to this part she broke off abruptly and asked – why in the world this interest in the past.

I was thus obliged to confess my insatiable curiosity about the people who lived in this house before us. Many were Madame V.’s ancestors; they had owned this property since the 1700’s and several other chateaux in the vicinity. When I reminded her that she’d once told me her grandfather bragged he could ride horseback from La Tourbeille to Bergerac and never leave his own land, she clapped her hands in surrender. “Come see me next week.”

And there in her house up river, in her ancestor-portrait dressed salon, she poured tea and served cake and brought out the parchment journal.

It was found in an attic here at La Tourbeille. The writer begins in 1761, the year he retires from the navy rather than joining the king’s war expedition to America, and recounts his stewardship of La Tourbeille. He has married Mademoiselle de La Tourbeille, the last of that family line and become the Intendant while her father was still alive.

Madame V. gave me a few pointers to understand the elaborately flourished penmanship, gorgeous but crabbed to make the most of the rare and expensive paper. When she laid it in my hands, fear and pleasure burned in equal measure. I was also astounded at her self control: not once did she ask me to be careful with this 230 year old, primary resource/family document that looked poised to disintegrate.

That night I raced to put the children to sleep so I could bed down with this marvel of 18th century accounting transactions and intimate family anecdotes, all mixed up and squeezed impossibly together. Monsieur l’Intendant notes details about his vinification work in the enormous winery, his trips down river to Libourne or Bordeaux to sell the wine, trips up river to his other properties to supervise tenant farmers on the planting of cereal crops for animal feed and bread, and inspections of his watermills on the Dureze where the wheat was processed. He waxes poetic about his favorite mare and the pleasure of finding the best stallion for her mating. He waxes even more poetic about the return of his 18 month old baby from the farm of her nourrice (wet nurse) and the obviously high quality of her milk since the baby came home round and pink as a rose. He rewarded the nourrice with a nice bonus and noted that sum neatly next to the price paid to the owner of the stallion. Less poetic but with perfect equanimity, he notes the continuing complaints of the servants who are fed up with “salmon for lunch yet again” (can you imagine the time when there was so much salmon in the Dordogne people could eat it every day?) Like most farmers he is dour about the weather, but in his case with good reason: the last quarter of the 18th century was a time of extraordinarily harsh winters when the river froze over, famine loomed, livestock died.

And intrepidly he goes on, recounting a worried visit to his father laid low by rheumatism and being treated with leeches, along side an argument with the smithy about shoes for his horses; he mentions the party organized around the baptism of a child next to purchases of farm equipment and a satisfactory bull; he cites a loan made to a neighbor next to this very brief mention: “Yesterday afternoon my wife went riding and was thrown from her horse. In the night she suffered a miscarriage.”

Deciphering the journal became a nocturnal obsession; a few pages unlocked at a time to keep rendez-vous with the people who once lived in these rooms. I fell asleep holding that parchment like a fragile relic, and the Intendant’s abbreviated notes became full blown narratives. The people took form. I slept in the attics with the chambermaids and complained about the summer heat, lugged water buckets to the well, perched on the foot stone at the grand portail to mount my horse, rode through the fields with the last Mademoiselle, handed my reins to a groom after a successful hunt, ushered the wet hunting dogs into their lodge and fired up the warming ovens below, planted a border of linden trees to mark the allée, fitted the salon with the new style Palladian windows, ordered the embellishment of the central staircase with stones from the Dordogne marked by fossils, tasted the rustic new wine at Christmas, lifted oak barrels in the chai and held massive ropes to roll them gingerly down the river bank for their journey to sale…

And eventually sat next to Monsieur l’Intendant as he wrote at his desk here – in this room, at this window, looking down at the river below.

For one glorious, dream filled summer this precious document was my closest companion. When I returned it to Madame V. in September, she understood the spell it could cast: “good material for your stories, n’est pas?”

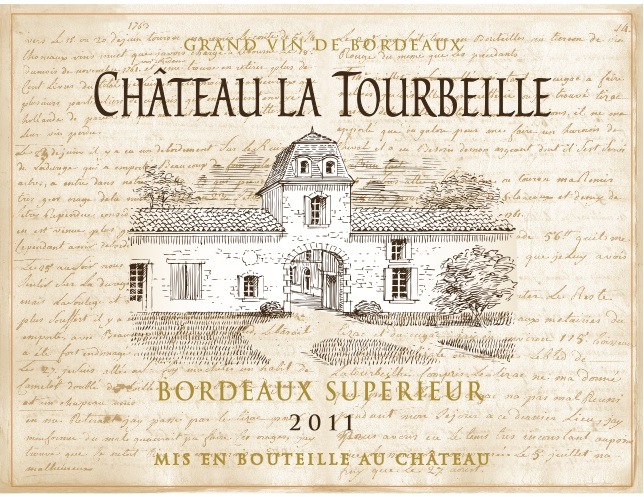

Good material for many things. When the time came to design the label for our maiden vintage, Chateau La Tourbeille 2011, the parchment journal leaped to mind. To us, La Tourbeille has always been a place of stories and intimacy. A place that invites you in to a secret garden. Not grand or imposing, rather a jewel of a place full of spirit and spirits, where you feel ensconced in several eras at once, cozy and at home, in a place many others have called home before us.

Here on the label, maybe you can see “Latourbeille” written just above “Supérieur” where the Intendent scribbled about his wine. As we now develop our enterprise, counting on the land, counting on our energy and counting on our luck, I often wonder if he is near by, perhaps one of the ancestors buried up in the field under the ancient boxwood trees. Wherever he lies, I take heart knowing there was an intelligent and energetic force valiantly shepherding this property through the very difficult years of the late 1700’s.

2 thoughts on “The Parchment Journal”

I am totally enchanted by your story.

Mary, Thanks for sharing your spirit(s) and the stories of La Tourbeille. I hear their voices through yours and look forward to meeting them and you again, soon.

best for 2013 from Camont- Kate